Junior colleges and NCAA lower-division schools begin to drop their football programs—in droves

In the process of updating our 2019 database of coaches’ contacts for every college football team in America, we became aware of a disturbing reality: the game of football is in decline.

Although the pace of football’s deteriorating condition may be slow and imperceptible to the casual observer, or even outright denied by practitioners and fans of the sport, make no mistake about it—the gridiron game is nearing critical condition. The game of football is dying. Ultimately, the game as we know it today will perish by way of the proverbial death by a thousand cuts.

Today, evidence of football’s morbid ascent to the top of history’s heap of forsaken traditions has never been more apparent than what occurred within the sport’s junior college (juco) ranks over this past year.

The bottom line is driving colleges to cut their football programs

Citing the high cost of maintaining football programs as the primary reason, Arizona became the first state to eliminate juco football when Maricopa County Community College District (MCCCD) ended the sport at all four of its campuses (Glendale, Phoenix, Scottsdale, and Mesa). The three remaining juco football programs in the state (Pima College, Arizona Western College, and Eastern Arizona College) soon followed suit.

All seven Arizona schools were members of the National Junior College Athletic Association’s (NJCAA) Western States Football Conference, leaving Snow College (Ephraim, Utah) as the sole remaining member in the conference.

The NJCAA represents one of the two governing bodies in the country for two-year juco football programs. The other junior college governing body is the California Community College Athletic Association, which regulates all junior college football programs in the state of California.

“As an essential resource to the community and businesses, MCCCD must be responsible for the financial resources it has been entrusted with,” said Matt Hasson, a MCCCD spokesperson.

The MCCCD stated that their cost to maintain football programs at the four juco schools totaled over $770,000 per year, which represented over 20% of the MCCCD’s total athletic budget and 50% of its insurance costs.

It’s this kind of common-sense language, reasoning and approach for why football as we know it in America is reaching critical condition.

When school administrators start to place in proper perspective their financial responsibility to safeguard public funds, alongside their true mission as an educational institutions—it spells serious trouble for the future of football. Consequently, school administrators across the country are now laying out the numbers and saying, “Folks, this is how much we spend on expenses for this sport, and this is how little revenue we take in. Something has to give!”

Football is simply too expensive and too dangerous to the health and safety of our students to make it a feasible proposition.

A recipe for a perfect storm for why American football is dying

Combine the rising cost of insurance and expenses to field a football team with the fact that the overwhelming majority of college football programs don’t make money. Then add to this volatile mixture, a growing chorus of community activists who are demanding accountability for how publicly-funded colleges are allocating their resources, and the health risks associated with the increasing scientific evidence regarding the long-term effects of football-related traumatic brain injuries. Stir them all up and you have a recipe for the perfect storm, whereby, the game of football may not survive. At least not in its present form.

Football is dying: A brief history of the beginning of the end of football

Since 1994, the game of football has faced unrelenting criticism and pressure from all quarters, with some calling for more stringent safety measures and even an outright ban of the game. 1994 is when the NFL first came under severe scrutiny for traumatic brain injuries due to accusations made by former prolific players like Dallas Cowboys QB Troy Aikman and San Francisco 49ers QB Steve Young and other prominent players who began to openly discuss their numerous concussions and the lack of adequate treatment they received throughout their careers.

1994 may mark the year future historians will declare as the beginning of the end of American football as it is played today, but it was long before ’94 when the American collective first became acutely aware of the inherent dangers of playing football.

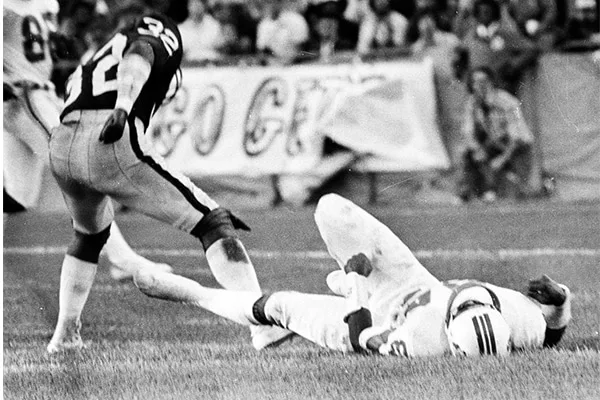

During an NFL pre-season game in 1978, New England Patriots wide receiver Darryl Stingley took a vicious hit to the head and neck area that was delivered by the notoriously hard-hitting defensive back Jack Tatum of the Oakland Raiders. The collision crushed Stingley’s cervical column, ending his 5-year NFL career and leaving him a quadriplegic for the remainder of his life. As a result of this tragic incident, over the next several years, the NFL introduced a series of major rule changes geared towards protecting the players from traumatic hits to the head area.

These new rules drastically changed the way the game had been played up until that point. However, it’s pretty evident that no matter how well-intentioned those rule changes—made nearly 40 years ago—they still didn’t go far enough. More importantly, all the rule changes that have been made since—and up until this very moment—are still not enough!

The ravages of the game remain today.

Fast forward to today, and not too many months will pass before we hear yet another former NFL player who has died and donated his brain to science. As a result, we discover that his brain —like so many others before—showed clear signs of damage due to the ravages of excessive head trauma.

Of course, there are many more sad and tragic stories from the game that we could list. The mountain of evidence is so powerful and overwhelming that some NFL players, who were making millions of dollars per year, are walking away from the game early. Because they don’t want to become “one of those stories.”

Cut after cut, the game is finally showing clear signs of the effects of the relentless slashes to its foundation. Football is dying.

In 2018, a National Federation of High Schools study revealed that over the past decade, the number of high school students participating in football had decreased by 6.6%.

Two-year junior colleges aren’t the only ones taking a butcher’s knife to their football programs. Over the past few years, several NCAA Division II and Division III colleges, as well as some privately-funded National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA) schools, have eliminated their football programs.

Each college administrator who justifies their decisions to cut their football program for the greater financial stabilization of the campus and safety of its students, makes it that much easier for the next college administrator to do the same. How much longer will it be before high schools across America begin to do the same?

The 2018 season may have set a record for the sheer number of colleges that cut their football programs, if such chronicles are kept. But how many more years like 2018 can the sport take before critical mass is reached?

Insurance costs will continue to rise, along with other expenses associated with fielding a football team. Community activists will continue to demand accountability from publicly funded educational institutions—at all levels—regarding how they allocate their resources. Scientific evidence of football-related traumatic brain injuries will persist. Many parents will continue to encourage their children to play sports besides football.

How much longer will it be before the game of football—as we know it—is no more?